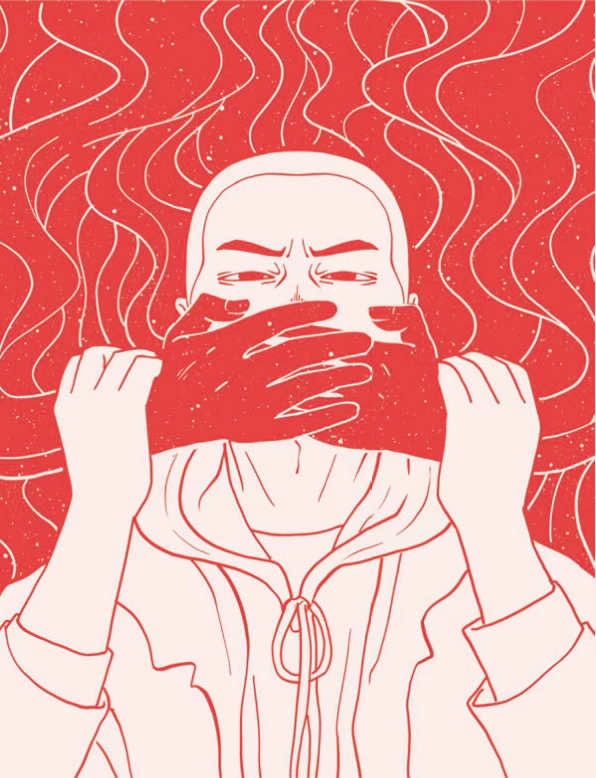

We are living in an age of silence

Sarah Shaffi on upcoming works that reveal and conceal our silences

Notable by Sarah Shaffi | Originally published in the print edition, October 11th 2024

We are living in an age of silence. Since the latest siege of Gaza – unprecedented in scale but the latest move in Israel’s ongoing occupation of Palestine – I’ve been thinking about the ways in which silence manifests and can be rendered through the language we use, or don’t. Silence is a black hole. It sucks in sound and action and throws out... nothing. Silence is not a peaceful or passive word, and within language, it finds formulations that sound sinister: Silence reigns. Silence suffocates. Silence strangles. Silence smothers. Silence is a weapon.

In Edward Said’s seminal text The Question of Palestine, rereleased by Fitzcarraldo Editions this October, the academic discusses the “denials of a very rigorous sort”

that Palestinians have been subjected to throughout modern history.

First denial, then blocking, shrinking, silencing, hemming in,” writes

Said, describing how Zionists have subjected the Palestinian people to erasure. We see this even now, with narratives of how the war began on October 7, 2023, rather than in 1948 with the mass displacement and dispossession of Palestinians from their homeland.

In Ibtisam Azem’s incredible novel The Book of Disappearance, translated beautifully by Sinan Antoon, she illustrates Said’s idea of silence as denial, through both a present-day storyline and a calling back to the 1948 Nakba. In the novel – released this summer – the disappearance of all Palestinians from their homeland overnight creates a silence that worries Israel’s government and citizens, who perceive it as a threat. But, up until their disappearance, these same people have been silencing Palestinians: changing road and town names to erase history, shutting down conversations about the past, silencing critics.

As the Palestinian character Alaa tries to fall asleep in “the silence and not the hush”, he thinks: “‘Hush’ has some peace of mind, but silence is like waiting for the unknown.” In The Book of Disappearance, silence is cold, it doesn’t respond, it haunts.

Azem’s novel illustrates the role which language – the words we use, who we choose to listen to or let speak, or the things we choose to discuss – plays in the breaking of silences. When the media opts for words like “died” instead of “killed”, for instance, when as a society we fail to name perpetrators or describe protestors as rioters, we blanket the truth with silence.

In Kay Sohini’s striking graphic novel This Beautiful, Ridiculous City – out in January – she writes about discussing the aftermath of a previous relationship with her current husband. She tells him that what had happened to her “...was complex. That it wasn’t abusive, and if it was, it was mutually abusive. After all, there was that one time I had hit him back.”

Sometimes we have to name a thing – for ourselves as well as others – for it to become real.

There are certain silences that Western society finds acceptable. In Radio Free Afghanistan, Saad Mohseni’s memoir (written with Jenna Krajeski) relaying his journey to setting up a free press after years of Taliban rule, we are told that the author’s mother “is a woman in a country that by conservative tradition or through government decree has so often tried to control women’s lives and silence their voices.”

When it comes to the lives of women in Afghanistan, in Pakistan, in India, in formerly colonised countries around the world, a Western sense of superiority can sometimes qualify which silences are deemed unacceptable. Where is this same strength of feeling for the women, the people, of Gaza? Where is this outrage when just a short boat ride away France bans the hijab – a physical manifestation of silencing – from public life? Where is this criticism when we read that in the UK, a man kills a woman every three days?

Writing – whether fiction or non-fiction – can help to break silences, even if the process can often be exhausting. As the poet Samatar Eli writes in the poem Coda, in his new collection The Epic of Cader Idris, out in November, some of us know that nothing good can come from “our deadly silence”.

In Forest of Noise, the essential poetry collection by Mosab Abu Toha (out in November), the Palestinian poet uses language to fight against those who would ignore his people’s plight. He does this even though, as he tells us in the poem No Art, he has personally “lost a city to darkness, and a language to fear”.

In the early days of the current attack on Gaza, the Palestinian poet Hiba Abu Nada wrote diary entries, which can be read in Daybreak in Gaza, (eds Muna and Teller). If nothing else compels us to use our words, then Abu Nada’s following request, made in an entry on October 9 – just 11 days before she was killed in an Israeli airstrike – should:

“Dear friends, we are entering a chapter in which we will be isolated from the world so that the city can be eradicated in the shortest time possible, a time when we won’t be able to communicate with anyone inside or outside the city. Night hasn’t fallen yet and the shelling is like hell. Until then cover us in a flood of prayer and send a message, or even a word, of steadfastness and freedom on our behalf.”